From BOFIT, on 16 February 2024:

PRELIMINARY FIGURES SUGGEST SURPRISINGLY ROBUST RUSSIAN GDP GROWTH IN 2023

last week released its preliminary 2023 data, which showed that Russian GDP grew by 3.6 % in 2023. Growth was clearly higher than either international or Russian forecasters had expected. For example, the most recent forecast published by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) last November estimated GDP would grow by about 2.5 % in 2023. The forecast update published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in late January said growth likely reached 3.0 % in 2023.

This year, Rosstat also released unusually rapidly a breakdown of GDP contributions on the demand and supply sides. Information on exports and imports, however, remained quite limited, making it more challenging to interpret the GDP data. While there are no clear indications of extensive and systematic statistical manipulation, the uncertainty surrounding the data and its inconsistencies have increased. We can be fairly sure that the Russian economy grew last year, but any specific growth figure should be taken with a high degree of caution.

DOMESTIC DEMAND DRIVES GROWTH AND SUPPORTS WAR INDUSTRY

Increased domestic demand was the driver of GDP growth. Preliminary figures show that public consumption rose by 3.6 % last year, i.e. the biggest gain in the history of current GDP reporting starting in 1996. Household consumption bounced back strongly from its dip in 2022. Fixed investment growth reportedly climbed by 10.5 % last year and inventory growth turned substantially positive. The foreign trade components are published only in current prices, which makes it difficult to capture the impacts of price changes. Russia’s isolation from the global economy is, however, evident in the decline in the share of exports, which corresponded to just 23 % of GDP last year – the lowest level in the current GDP statistical series starting in 1996.

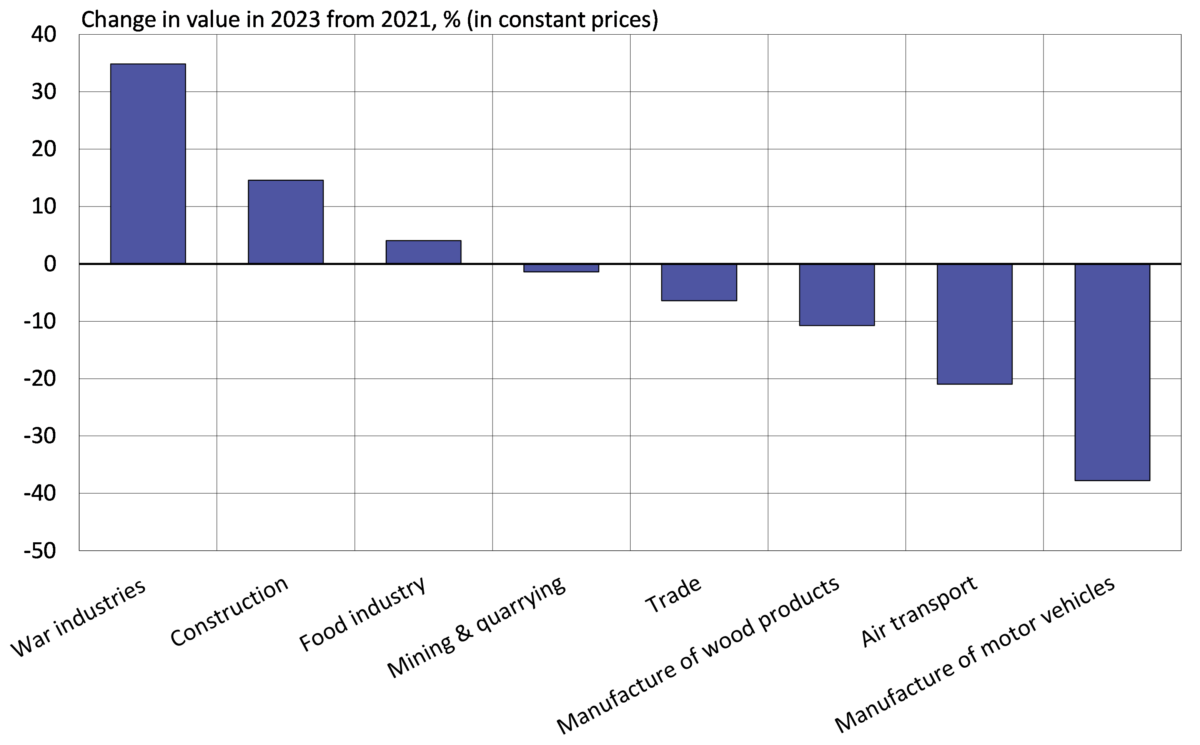

On the supply side, increasing domestic demand has fuelled growth in industries linked to the war effort, construction and retail sales. Industries serving the war effort and the construction industry have grown rapidly during the past two years and their 2023 output figures were much larger than in 2021. Manufacturing growth, in particular, has relied largely on war-related industries. Output of manufacturing branches contributing to the war effort last year were up by roughly 35 % from 2021, while other manufacturing branches as ana aggregate were down by 0.4 %. Even with economic recovery, many industries such as car manufacturing and air transport last year experienced output well below pre-war levels.

Russia’s GDP growth has been led by war-related manufacturing industries and construction sector

Note: War industries is a proxy measure consisting of manufacturing branches linked to the war effort (manufacturing of fabricated metal products, electronics and other transport equipment).

Sources: Rosstat, BOFIT.

OUTPUT GROWTH CONTINUES TO SLOW

Monthly data suggest that output growth has slowed in recent months. Industrial output, retail sales and other services have remained flat for many months. Only construction appears to have showed sustained growth at the end of last year.

…

Recent forecasts see Russian GDP growth slowing this year. The CBR released its new forecast today and expects GDP to grow 1-2 %. The IMF forecasts GDP growth of 2.6 % and the OECD 1.8 %. The Consensus Economics average of forecasts released in January anticipated growth of 1.7 % this year.

From Mark Sobel, US OMFIF Chari, formerly US Treasury, 12 February, in “Russian economic ‘resilience’ is not what it seems”

Don’t overestimate the size of Russia’s economy

Russia’s war footing and the associated fiscal expansion is a clear driver of the economy’s current solid activity. According to draft plans from the government, Russia is increasing real military spending this year by almost one-third, accounting for over a third of spending and around 7% of gross domestic product.

But one should not overstate the economy’s size and vigour. As a share of the global economy, Russia has fallen in purchasing power terms from nearly 4% before the 2008 financial crisis to under 3% (and using market exchange rates to now well under 2%).

Oil proceeds are a crucial revenue source. Russian officials have indicated that Brent crude should be $85 per barrel in 2024. However, Brent has traded below that level so far this year. Moreover, Urals oil trades at a significant discount to Brent, and there is enormous opacity surrounding the discounted price Russia receives as it is highly dependent on deals with China and India.

US and G7 efforts to reinforce the oil price cap and curtail sanctions evasion (for example by Greek tankers) will also impact revenue. They unfortunately have not hurt the Russian economy anywhere near as much as desired.

While Russia should be able to easily finance its deficit, several costly macro factors come into play. Inflation is elevated and the central bank is maintaining high interest rates in the light of the outlook for prices. That will erode real incomes and crimp investment. The ruble will on average weaken as currency depreciation generates more rubles for the budget. The currency would in all probability weaken much further were it not for capital controls. Russia also will presumably draw down on the National Wealth Fund.

More generally, the Russian economy can be increasingly characterised as a system of energy production financing surging military spending, with little innovation elsewhere in a society already well behind others on the technological frontier. But, of course, the reliability of economic data should always be taken with a pinch of salt, and especially Russian economic data in the current circumstances.

Geopolitical vulnerability

Russia’s growing dependence on China, India, Iran and others is a vulnerability beyond energy market developments. India is strengthening relations with the US. China wishes to maintain strong export ties to the US and Europe. Notwithstanding cheap energy, China and its firms will be cautious in their Russia dealings, fearing that they might run afoul of US sanctions, especially those that could block access to the US financial system.

In the meantime, Russia’s human capital is being sharply eroded. The death of soldiers (estimates suggest over 300,000 soldiers killed or badly wounded) and an enormous brain drain (estimated up to 1m, the bulk of whom are young and well educated) are imposing a huge loss of human capital and reportedly straining labour markets. These factors will harm Russian productivity well into the future.

Western sanctions on technology, even if significantly circumvented because of transshipments and other leakages, are hurting the economy. Reports abound about the lack of spare parts – for example, the difficulties in fully keeping Russian airplanes afloat. Russia will also face difficulties developing many energy fields without western services.

The opportunity cost of the war footing is also seen in the numerous reports of burst pipes and the loss of winter heating throughout Russia as basic infrastructure needs go unmet.

See also Martin Sandbhu in FT (Feb 11).

Here’s my August blogpost attempting to determine what growth ex-military spending would look like in 2023.