Much has been written about the July 13, 1882, death of Arizona Territory gunfighter Johnny Ringo, most of it wrong. Writers have inserted their assumptions as facts. Thus, the story often goes that Johnny found himself alone in a trackless waste on a hot day in mid-July without water. Despondent, his horse having run off, left without water, Ringo committed suicide.

In fact, Ringo died within 20 yards of a well-traveled road, having just reached Turkey Creek, the first available water source within many miles. He was within a quarter mile of the ranch of B.F. Smith, in the western foothills of the Chiricahua Mountains, and those on the ranch heard the shot that killed Johnny. Furthermore, July is a month of monsoon rains. In Arizona that means the wind comes from the southwest, from the Pacific and Gulf of California, bringing almost daily thundershowers that fill ponds and cause washes and streams to run. The rain cools the land, which at Turkey Creek is at 5,400 feet elevation—a far cry from the blazing desert around Phoenix, at 1,100 feet.

As the Epitaph account reveals, Yost estimated that within a quarter hour 11 men were on the scene. They comprised a “coroner’s jury.” That term may mislead present-day readers. These were 11 everyday men who reported their findings to the coroner in Tombstone by letter. They had no forensic training. They were in a hurry to be done with the affair and get back to work, to bury a body already starting to stink. They did not wish to be called to Tombstone, miles distant, for lengthy court proceedings.

(A.O. Tucker)

Ringo was known to several of the men. The Epitaph published their findings. Johnny was found in a seated posture leaning against a tree. His boots were missing. “He was dressed in [a] light hat, blue shirt, vest, pants and drawers. On his feet were a pair of hose and an undershirt torn up so as to protect his feet.” He wore two cartridge belts, one for pistol and one for rifle. The revolver belt was upside down. There was no holster for a pistol, nor was it a Buscadero rig. His rifle propped against a nearby tree, his pistol clasped in his right hand. There was a bullet hole atop the left side of his skull. “A part of the scalp [was] gone,” the paper noted, “and part of the hair. This looks as if cut out by a knife.” There was no mention of powder burns or stippling on his head.

Black powder burns slowly and keeps burning as the bullet emerges from the barrel. In his 1966 song “Mr. Shorty,” Marty Robbins sang, “The .44 spoke, and it sent lead and smoke, and 17 inches of flame.” This isn’t far off the mark. A close-range pistol shot with muzzle held to temple likely would have ignited Ringo’s hair and left an awful mess. The coroner’s jury might have left such details out of their report to spare family members and the public, or perhaps because they simply didn’t think it important. After all, the effects of close-range pistol shots was common knowledge in that era.

The Epitaph report surmised the circumstances:

“The general impression prevailing among people in the Chiricahuas is that his horse wandered off somewhere, and he started off on foot to search for him; that his boots began to hurt him, and he pulled them off and made moccasins of his undershirt. He could not have been suffering for water, as he was within 200 feet of it, and not more than 700 feet from Smith’s house. Mrs. Morse and Mrs. Young passed by where he was lying Thursday afternoon, but supposed it was some man asleep and took no further notice of him. The inmates of Smith’s house heard a shot about 3 o’clock Thursday evening, and it is more than likely that that is the time the rash deed was done. He was on an extended jamboree the last time he was in this city.”

The following Tuesday Ringo’s horse was found with one of his boots still hanging from the saddle. The Chiricahua folks were mistaken. Johnny hadn’t, while searching for his horse, taken off his boots because they hurt. He still had the horse when he took them off. The strips of undershirt wrapped around his feet were clean, not dirtied by any walking about. He was close to water and aid, not helpless and alone in a desert. The newspaper also noted Ringo was subject to frequent melancholy and had abnormal fear of being killed. He was paranoid, but that doesn’t mean people weren’t pursuing him with the intent to do him harm.

What Really Happened on Turkey Creek?

The spot where Ringo was found, sitting beneath an oak tree on the banks of upper Turkey Creek, is idyllic, shaded and alive with the sound of trickling water. Though peaceful, it was not at all secluded. It was on the road to Galeyville, which passed a nearby pinery and sawmill. Several passersby spotted Johnny’s body, each believing he was only resting.

In his 1927 book Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest author Walter Noble Burns added several details. “[Ringo’s] six-shooter, held in his right hand, had fallen into his lap and caught in his watch chain,” Burns wrote. “Five chambers of the cylinder were loaded; the hammer rested on the single empty shell.” Of course, Burns was writing an adventure tale and not a history. Nonetheless, some four decades after Johnny’s death he did conduct research in Tombstone and Cochise County, speaking to people who had direct knowledge of the events.

The spent cartridge may mean Ringo had fired the fatal shot. However, it could easily be symptomatic of resting the hammer on a spent cartridge for safety. As a young Wyatt Earp once learned to his chagrin, resting the hammer on a live cartridge could lead to accidental discharge of the weapon; in his case, as he leaned back in a chair, his revolver tumbled from the holster and landed on the floor. That Johnny’s pistol was resting in his lap, tangled in his watch chain, is more intriguing. It’s hard to imagine the pistol, had he shot himself, falling in that position instead of at his side. Forensic studies show that suicides often continue to grip the weapon, so that by itself is not evidence of postmortem tampering by a third party. As Ringo lacked a holster for his pistol, he must have worn it tucked beneath his cartridge belt. Thus, in a seated position, it might well have become tangled as he tried to draw.

(Doug Hocking)

There is much peculiar in how Johnny was clad. He’d taken off his boots and hung them from the saddle of his horse, which wandered off. He’d also taken the time to strip off cartridge belts, vest and shirt, then removed and torn up his undershirt to bind his feet. Walking barefoot in Arizona is a painful experience at best. Stones, cacti and stiff grass, not to mention various critters and the hot ground, make such barefoot forays ill-advised. Cowboys do not, as some have written, hang their boots from the saddle to keep out scorpions. On reaching a destination, they remove the saddle from the horse, placing it on the ground, and then wipe down the horse with dry grass. Moreover, Johnny had re-dressed himself, buckling on his cartridge belts (one upside down) and binding his feet as if preparing to pursue his horse.

That leaves the question of why he took off his boots in the first place. Let’s consider his situation. He’d been on an extended spree in Tombstone. When friend Billy Breakenridge met Ringo at South Pass in the Dragoons, Johnny had two bottles of whiskey and offered Billy a drink. By the time he was approaching Turkey Creek, Ringo had crossed many dry miles and was either severely hungover or still drunk. He and his horse both needed a drink of cool water. It seems likely Ringo took off his boots and hung them from the saddle to keep them dry while he waded into the creek to cool his feet and splash water on his face. Likewise, the horse would have waded in for a drink.

What came next is an educated guess. The horse panicked and broke away at some sound in the dense brush. It might have been a bear or someone stalking Ringo. In any event, Johnny had to chase down his horse and didn’t care to do that barefoot. He climbed the steep bank to the tree where he was found, undressed himself to remove his undershirt and then re-dressed, wrapping his feet in preparation for a long walk.

At that moment one of two things occurred. Suddenly despairing of catching his horse, Ringo resolved to kill himself. He must have been certain succor would not have been available at Smith’s ranch or from the many passersby. Alternatively, the noise from the brush that had startled his horse might have been someone stalking him. That someone climbed the bank while Ringo was distracted with his clothing. Hearing the approach of a stranger, Johnny reached for his pistol. The stranger, still only partway up the slope, fired upward from a distance of 10 feet or more, striking Ringo in the temple, the bullet emerging from the top of his skull. The stranger then took out his knife and carved off part of Johnny’s scalp as a trophy.

Who Could Have Done It?

The above proposed scenario for Ringo’s final hour accounts for all the evidence, providing a logical explanation for much that was odd in how he was found. As to whether Johnny suddenly decided to kill himself after losing his horse or was killed by a third party, who can say? Murder seems plausible, maybe likely.

There are many candidates for Ringo’s murderer. Some think Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday might have been responsible. They could have been there. If Constable Fred Dodge, acting as their spy in Tombstone, had telegraphed that Johnny was on a binge and would soon return to Galeyville and his San Simon ranch, there would have been time for Earp and Holliday to travel over by train, especially given Johnny’s circuitous ride home. Even taking an indirect route, the pair could have made the trip by train. The mouth of Turkey Creek was a choke point, by which Ringo would have passed within a few hundred feet. However, a secret only remains a secret if only one person knows it. Wyatt and Doc surely would have been recognized as they left the train. Many co-conspirators would have to have been brought in on such a plan.

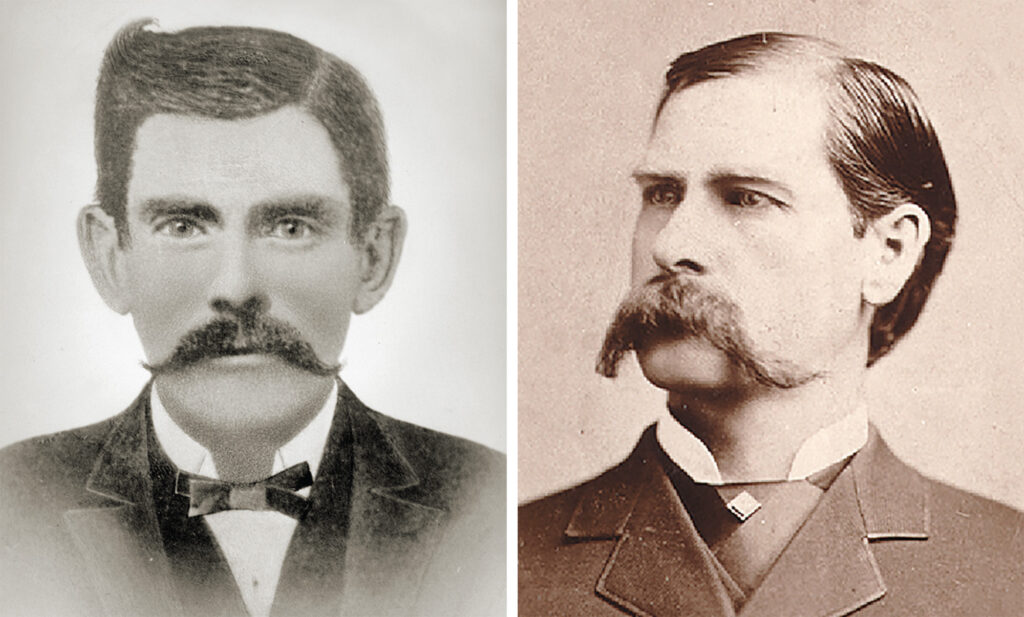

(Left: Denver Public Library; Right: Wild West Archive)

Most other candidates seem even less likely, due to implausible motives. Except for Buckskin Frank Leslie.

Leslie appears nowhere in the historical record before 1878. He arrived in Tombstone in 1880, a man in his late 30s who had adopted the persona of an Army scout, which he claimed to have been for more than a decade. Yet, there is no evidence he was a scout before moving to Tombstone. Buckskin Frank was a congenial sort of fellow around the campfire, which probably accounts for his acceptance as a scout on later expeditions. In 1885 he was hired to guide Captain Emmet Crawford’s command in pursuit of Geronimo but was, according to Los Angeles Times reporter Charles F. Lummis, “directly discharged because of his inability to tell a trail from a box of flea powder.” Leslie also served as a dispatch rider, bringing “wildcat dispatches” to Tombstone, his presumed skill scoffed at by Crawford’s superior, Brig. Gen. George Crook.

Lummis, who met Frank in Tombstone, probably had the right of it in his 1886 Times article:

“Leslie is a peculiar case—one of the types of a class not infrequently met on the frontier. A man apparently well educated, gentlemanly and liked by all who know him; with as much “sand” as the country he ranges—but a novelist who can make a little truth go as far as anyone in the territory.”

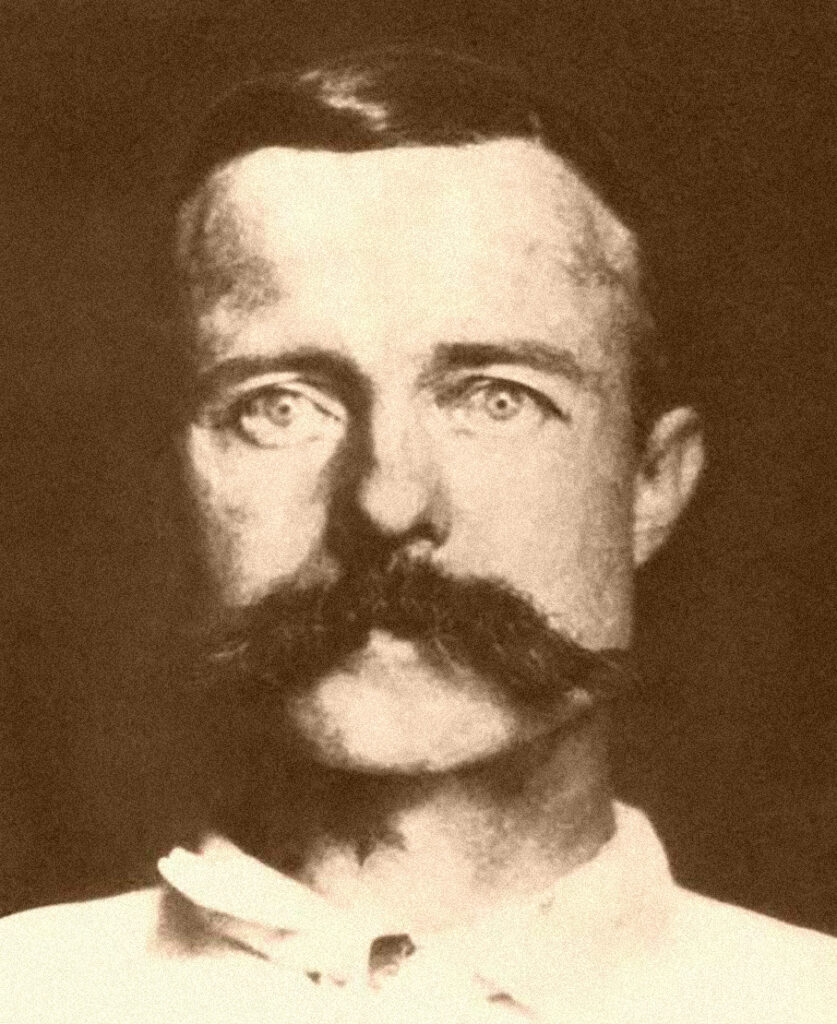

(Legends of America)

In the spring of 1880, a few weeks after Cosmopolitan Hotel chambermaid Mary Jane “May” Evans married, she took up with Leslie—neither, apparently, being respecters of the sanctity of matrimony. That June 22 May’s husband, Mike Killeen, was mortally wounded—probably by Frank, though under confusing circumstances—and scarcely a week later May was Mrs. Frank Leslie. The marriage was not a happy one, as Frank, a womanizer, strayed. Perhaps May had seen through the false front and threatened his he-man persona. That might explain the abuse she suffered at his hands.

In 1881, while Earp and friend Holliday temporarily cooled their heels in jail after the gunfight near the O.K. Corral, Doc’s longtime companion Big Nose Kate twice gave Ringo a tumble. Johnny, too, was no respecter of other men’s territory, and the following spring he and Frank were at loggerheads over a woman.

In July 1882, as Ringo returned from his extended spree in Tombstone, witnesses spotted Leslie trailing him near Turkey Creek. That November 14 Johnny’s friend Billy Claiborne, who’d fled from the O.K. Corral fracas, picked a gunfight with Leslie after Frank ejected him from a saloon for obnoxious drunkenness. Claiborne ended up dead in that fight. At the time some said Billy had accused Frank of killing Ringo, while years later multiple sources claimed Leslie boasted of having killed Ringo. Taking a scalp trophy would have fit right in with his persona.

Leslie’s life only took a downturn from there. By 1889 he and May had divorced, and Frank had absconded to his ranch in the Swisshelms with former prostitute “Blonde Mollie” Edwards, a younger woman. That July 10, on returning home after a spree, Frank entered the ranch house to find Mollie and a young ranch hand in discussion. Drawing his gun, Frank killed Mollie and wounded the ranch hand. No motive was given, but Mollie had mentioned wanting to return to “city life” in Tombstone, and perhaps 40-something Frank was feeling his age and believed she was sweet on the boy. Though no respecter of other men’s prerogatives, Frank was jealous of his own. Pleading guilty to first-degree murder, he was transported to Yuma Territorial Prison in January 1890. On Nov. 17, 1896, having serving nearly seven years behind bars, Leslie was pardoned by Arizona Territory Governor Benjamin J. Franklin.

In 1916, after two decades of further adventures and failed marriages, Buckskin Frank Leslie was interviewed by a reporter from The Seattle Daily Times. He stated his age as 74 and said he was planning a trip to Mexico. When and where he died is anyone’s guess, as he vanished from the record as suddenly as he’d appeared on it.

For further reading, author Doug Hocking recommends “Buckskin Frank” Leslie, by Don Chaput; They Called Him Buckskin Frank, by Jack DeMattos and Chuck Parsons; and John Peters Ringo: Mythical Gunfighter, by Ben T. Traywick.