[ad_1]

PBoC and financial regulators act, but even with fiscal measures underway, are unlikely to drastically change the path of the economy.

As summarized by Bloomberg:

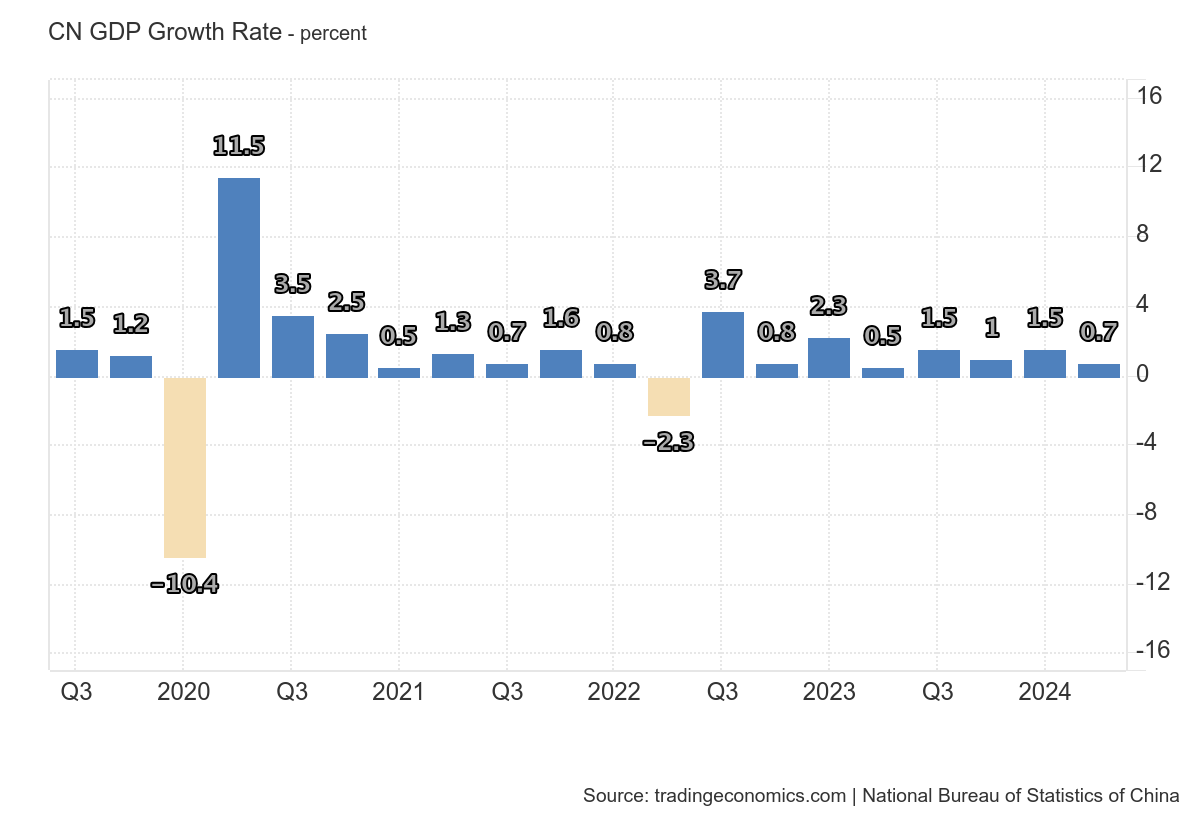

To me, it’s curious it took so long, then followed by a flurry of activity in the last 48 hours preceding the announcement. I have no particular insights into the workings of policymakers under the current regime, so I’ll let others debate the sources of delayed action. However, here are some macro indicators that show the need for some action — decelerating growth, and deflation. First GDP growth (q/q SA):

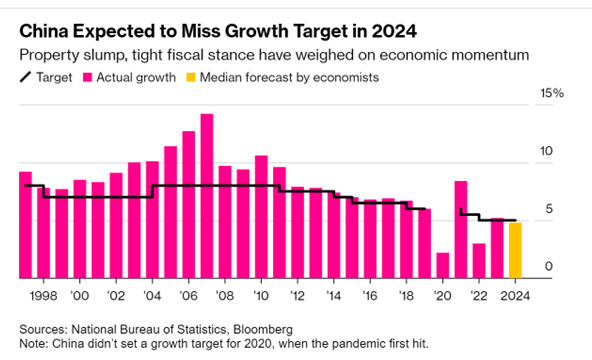

Taken at face value, 0.7% q/q is 2.8% annualized(!). There were doubts that under previous set of macro and regulatory policies, the 5% target (y/y I think) would be hit.

Source: Bloomberg, 24 Sep 2024.

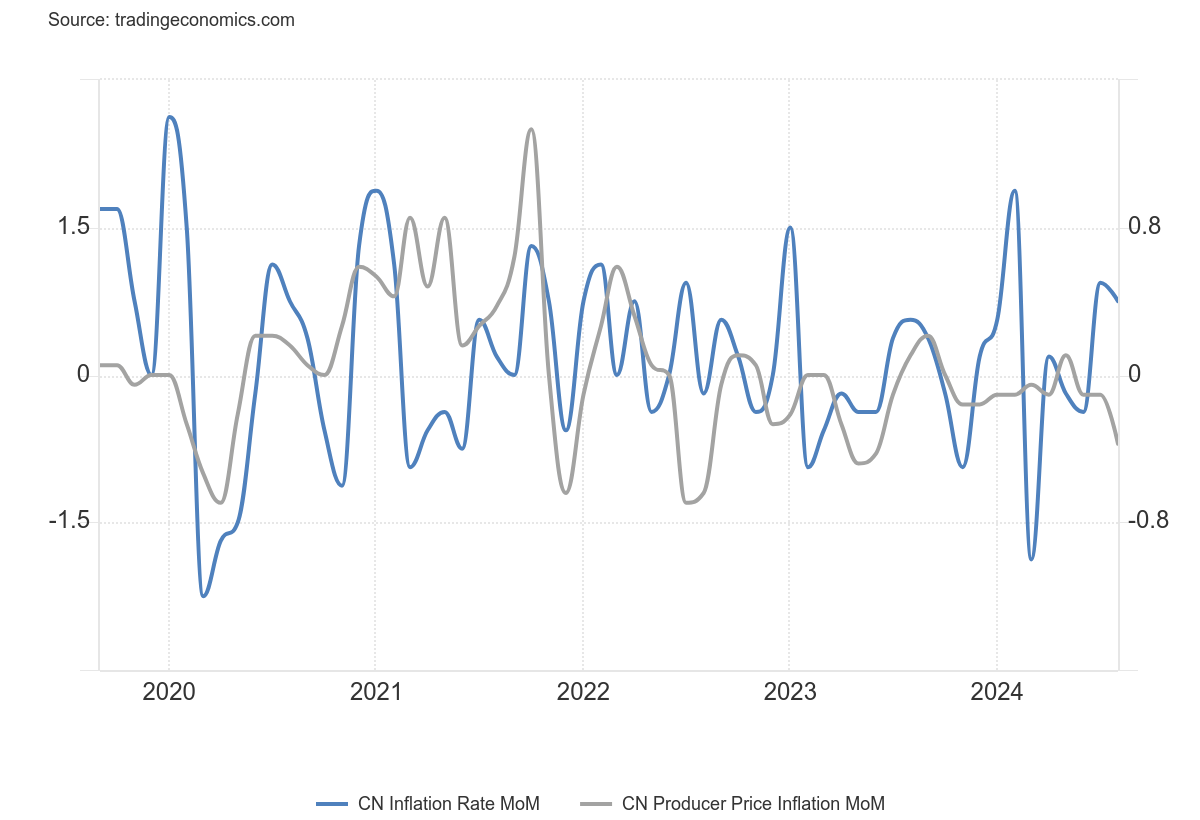

Second, deflation. More worrying in some ways is the decline in prices — not in the CPI but at the producer level, and for the economy overall. CPI and PPI m/m inflation rates (note difference of scales, left vs. right axes). Deflation can be a signal of slowing growth, as well as exacerbating demand shortfalls.

So while consumer prices have risen in recent months, producer prices have fallen. As noted in the Bloomberg article, the GDP deflator has also fallen, for five straight quarters (-3.8% 4 quarter change as of Q2).

The quandary is shown in the decomposition of GDP:

Source: Garcia Herrero & Xu, Natixis, 13 Sep 2024.

Despite the fact that the above is a mechanical decomposition (an accounting identity), one can still make some inferences about the constraints to growth. Consumption is the main contributor to growth – but consumers are reluctant to spend in the wake of the collapse of the housing sector. Deflation makes debt more burdensome (think of the financial accelerator). Net exports could contribute more to GDP, but with the surge in Chinese exports already eliciting trade barriers not only in the US, but also in Europe, it’s hard to think of a big increment coming from additional net exports.

What will fix things? It depends what “fix” means. Return to +5% growth? Or just continued growth without collapse. I think the consensus view is +5% growth is off the table. So avoiding a full-blown crisis, with hopefully positive growth rates is the goal.

Eswar Prasad notes the need to accelerate productivity growth (which affects the long run, but — depending on how implemented — also the short run via expectations):

Recognizing the need to improve productivity and shift away from low-skill manufacturing, the government recently articulated a “dual circulation” growth policy, which augments continued engagement with global trade and finance with greater reliance on domestic demand, technological self-sufficiency, and homegrown innovation. But the approach has run into difficulties. China still needs foreign technology to upgrade its industry, and rising economic and geopolitical rifts with the United States and the West could limit China’s access to foreign technology and hi-tech products, as well as to markets for its exports. Moreover, the government’s recent crackdown on private firms in sectors such as technology, education, and health has had a chilling effect on entrepreneurship.

The ongoing decline in inward FDI suggests there’s been no reversal in the conditions for FDI into China – unsurprising given the Xi administration has not really changed the overall economic framework, including “dual circulation”. (Of course, FDI into China might have also occurred because of attempts to friendshore, as well as the prospect of restrictions of governmental restrictions on outbound FDI).

So, don’t look for a quick fix. And expect even less, if the Xi administration continues to place primary weight on political dominance versus GDP growth (see e.g. Arthur Kroeber ).

[ad_2]

Source link